Wealthtender is a trusted, independent financial directory and educational resource governed by our strict Editorial Policy, Integrity Standards, and Terms of Use. While we receive compensation from featured professionals (a natural conflict of interest), we always operate with integrity and transparency to earn your trust. Wealthtender is not a client of these providers. ➡️ Find a Local Advisor | 🎯 Find a Specialist Advisor

Although dividend investing and chasing yield are popular among investors, that focus is fundamentally flawed. It should be considered more of a “feel good” strategy than a good strategy. In this article, I will explain why dividends are irrelevant and dividend investing is irrational.

What Is a Dividend?

A dividend is a method for a company to distribute earnings to its owners. At some point, a profitable company will end up with a residual amount of cash on the books. Management can choose to do one of two things with this accumulated profit –

- Reinvest into the business: new factory, expand to new markets, pay down debt

- Distribute cash to shareholders via share repurchase (buyback) or dividend

We can evaluate each option in the context of the fundamental accounting formula:

A = L + E (assets equals liabilities plus equity)

As shareholders, we are most interested in maximizing our equity value, so we rearrange the formula to:

E = A – L (equity equals assets minus liabilities)

This is very similar to individual net worth, but we’re looking at company “net worth”.

What Effect Does Company Reinvestment Have on Stock Value?

Initially, reinvestment has a neutral effect on equity – the company exchanges a cash asset for a capital asset or an equal reduction in liabilities. The business usually reinvests to generate growth in the future, and this is a common strategy for growth companies like Amazon, Facebook, etc.

The market may perceive this company investment as a positive sign, increasing growth expectations and raising the present value of the stock.

What Effect Does a Share Buyback Have on Stock Value?

A share buyback has a neutral effect on equity.

Cash leaves the balance sheet to buy company shares. This reduction of assets (cash) reduces total equity value, but shares outstanding decrease, and equity value per share increases proportionally. So, the net effect per share is flat.

A good analogy is a pizza cut into six slices vs. eight slices – if you own half the pizza, it doesn’t matter if that’s 3 large or 4 small slices. The proportion of ownership and the value is the same.

What Effect Does a Dividend Have on Stock Value?

A dividend has a negative effect on equity as of the ex-dividend date (the owner on that date is entitled to the dividend a few weeks later).

This is because cash paid as a dividend leaves the company’s balance sheet and gets paid to shareholders. Typically, companies pay dividends when they have limited opportunities to invest internally for growth, distributing profit to investors instead.

Wait! What happened with dividends?

All the options seem fine except dividends which cause a very real and very negative drop in equity value! Why does share value drop from the dividend?

Think about a hypothetical scenario where you have a business for sale in your town with a fair value of $1M that happens to have $100K cash in its bank account. What would happen if the current owner decided to empty the account before the sale? What would the business be worth now?

You guessed it, the business would now only be worth $900K since it has $100K less in assets.

Dividends Are Not a “Bonus” Because Equity Value Drops by the Dividend Amount

This time, let’s explore some math from the investor’s perspective.

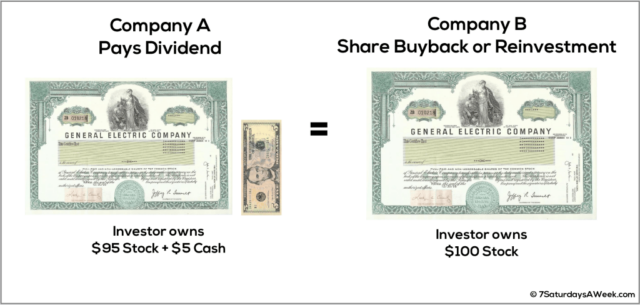

Company A and Company B are both worth $100 per share with 100 shares outstanding and have $5 per share to distribute. Company A chooses to use dividends, and Company B uses share repurchase (buyback).

Per-share value of Company A is easy: pre-dividend = $100, post-dividend = $95

Per-share value of Company B is a little more complex – The company will part with $5 per share in cash which will buy $5 x 100 or $500 worth of stock, equivalent to 5 shares.

Reducing the value of Company B by 5% and decreasing the number of shares outstanding by 5% will net each other out, and per-share value remains at $100. This is the same value that Company B would have if it chose to reinvest profit back into the business.

Effectively, the dividend investor who owns Company A stock is in the same position as a company B investor who decided to sell $5 worth of his shares.

A Dividend Is to the Investor Equivalent to a Forced Liquidation of Stock

The only difference is that the Company B investor gets to choose when and how much stock is liquidated – Company A management chooses for their investors. The Company A investor can also choose to reinvest the dividend and bring their total equity back up to $100 – same as the company reinvestment and buyback scenarios.

Dividends Are Irrelevant Because an Investor Can Create a “Homemade Dividend” at Any Time by Selling Appreciated Shares

Given what we’ve discussed above, a rational investor should be indifferent to income return (dividend) vs. growth return (capital gains). Modigliani and Miller figured this out back in 1961.

Total Return = Income + Capital Gain

Total return is what ultimately matters since a capital gain can be turned into a dividend, or a dividend can be reinvested to be a future capital gain. Dividends are not magic – they are just one component of total return.

Okay, so we’ve established that dividend vs. capital gain is irrelevant because they’re interchangeable. Despite this, many investors narrow their investment selection to only high dividend payers – 4% and above.

Why Is Focusing on High Dividend Stocks Irrational?

1) Tax Drag

In a taxable account, dividends create tax drag which lowers long-term returns. Tax drag occurs because realized dividends are taxed every year and the tax paid reduces the amount that can be invested. Higher dividends and longer investment horizons will cause more tax drag, so capital gains are preferable to dividends in non-qualified accounts. Deferring tax is always better than realizing it every year if rates are the same.

An investor can defer realizing capital gains until they have offsetting losses or until they are in a low-income year, harvesting those gains at 0%. They have no such control with dividends.

Additionally, under current law, capital gains can be deferred until the original owner’s death at which time the heirs receive a “step up” in basis and can sell immediately with zero tax. Tax drag does not apply in tax-sheltered accounts like 401(k), IRA, etc. or if the investor is currently at or under the 12% bracket paying 0% on qualified dividends and capital gains.

Pro tip: Generally, it’s best to hold higher-income assets like high-dividend stocks or REITs in tax-sheltered accounts to minimize tax drag.

2) Avoiding Growth Companies

Growth companies typically reinvest a large portion of their cash back into the business rather than distributing cash to shareholders. The top 10 US companies by market cap (total equity value) and their dividend yields are: Apple (0.50%), Microsoft (0.79%), Google (0%), Amazon (0%), Tesla (0%), Facebook (0%), Berkshire Hathaway (0%), Nvidia (0.06%), Chase (2.39%), and Visa (0.7%).

Notice that half pay zero dividends, and the top payer (Chase) pays a paltry 2.39%, barely above the index as a whole. Warren Buffett, CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, has said that his three priorities for cash are reinvesting into the business, making acquisitions, and buying back stock (page 19). No dividends.

Since 1926, dividends have only been responsible for about one-third of the total return of the S&P500 with capital gains contributing the remainder. Capital gains are clearly an important component to total return!

If you filtered out these enormously successful companies based on their lack of a high dividend (or a dividend at all), it would mean missing out on the portfolio boost that their explosive growth has provided!

3) Falling Into a “Value Trap”

High dividend payers (4%+) choose to distribute a higher proportion of their earnings than the broad index (~2%), which means less cash available for the company to invest in growth opportunities. These mega-yield companies are often operating on mega debt and can be one recession away from bankruptcy.

High yield can result from 1) paying high dividends or 2) falling market value. The latter results in a “value trap”, when a company looks attractive from a P/E or dividend yield perspective, only because the price is falling faster than earnings or dividends. A nosedive in the stock price will cause P/E to decrease and D/P (dividend yield) to increase.

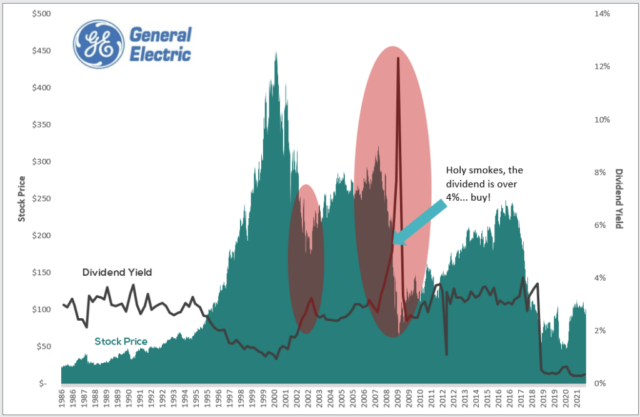

Keep in mind that every bankrupt company was a value trap on its way down. General Electric is a great example to show how stock price affects dividend yield:

Notice the spikes in dividend yield (right axis) often correlate with a decrease in stock price (left axis). An unsuspecting dividend investor, lured in by the rising dividend circa 2008, would have enjoyed falling prices which caused a 5% dividend followed by one over 12%… and ultimately, disaster.

4) Portfolio Concentration

Selecting high-dividend companies will concentrate a portfolio into a subset of sectors/market segments/risk factors. Typically a portfolio of dividend stocks will have a heavy emphasis on market and value factors while tilting toward large-cap companies. These factor exposures are much more predictive of portfolio returns than a measure like dividend yield.

Diversification within and across asset classes is key to ensuring your share of market returns. Unless you have an information advantage over the millions of other investors, how can you expect to generate outsized (total) returns by simply focusing on dividends?

If something as simple as current dividend yield or dividend growth were an indicator of higher risk-adjusted returns in the future, it would quickly be identified and arbitraged away.

Why Do Investors Focus on Dividends and Not Total Return?

There’s the million dollar question. The answer is that it’s likely the result of several factors.

First, humans all display some degree of mental accounting bias which causes us to treat equal sums of money differently based on their source. One example of mental accounting is treating a bonus or tax refund (trip to Cabo?) differently than a regular paycheck (bills and savings), even though dollars are all the same (fungible).

A preference for income rather than growth (which a shareholder can turn into income at any time) is an excellent example of mental accounting. Investors sometimes view a cash dividend as a “bird in the hand” whereas a future capital gain is uncertain.

Many novice investors seem to view dividends are the only source of equity return and completely ignore capital gains in the total return equation, not understanding that a dividend paid equals a lower share price.

Additionally, people often perceive dividends as “lower risk” than capital gains – in fact, many investors believe high dividend stocks are an effective bond substitute in this low interest rate regime. However, this is misguided as firms often cut dividends during economic slowdowns. The dividends cause an even more significant price decline than if the company reinvested that cash or bought back shares. Remember – to the investor, a dividend is equivalent to a forced liquidation.

As far as a substitute for bonds? Dividend stocks are still stocks, highly correlated with the overall market. When stocks crash during a recession, dividend stocks are also crashing. This is precisely the time when you need the diversification benefit of other asset classes as a portfolio ballast.

Pro tip: If everything in your portfolio is often up (or down) at the same time, you’re not really diversified

Conclusion

Dividends are not a magic bullet. Narrowing your investment universe to focus on them can cause serious portfolio issues, including tax drag, overconcentration, and missing growth. Since dividends are irrelevant, focus on total return and consider potential additions to your portfolio in the context of how they affect risk and return of the entire portfolio – not in isolation.

This article was originally published on 7 Saturdays a Week and is republished on Wealthtender with permission. This article reflects the insights and opinions of its author and is not a recommendation or endorsement of their views or services.

About the Author

Allen Mueller

Allen is the founder of 7 Saturdays Financial, a modern flat-fee planning firm based in Dallas, Texas. He leverages technology to serve families nationwide and specializes in helping busy professionals achieve early financial independence.

Wealthtender is a trusted, independent financial directory and educational resource governed by our strict Editorial Policy, Integrity Standards, and Terms of Use. While we receive compensation from featured professionals (a natural conflict of interest), we always operate with integrity and transparency to earn your trust. Wealthtender is not a client of these providers. ➡️ Find a Local Advisor | 🎯 Find a Specialist Advisor