Wealthtender is a trusted, independent financial directory and educational resource governed by our strict Editorial Policy, Integrity Standards, and Terms of Use. While we receive compensation from featured professionals (a natural conflict of interest), we always operate with integrity and transparency to earn your trust. Wealthtender is not a client of these providers. ➡️ Find a Local Advisor | 🎯 Find a Specialist Advisor

In my early 20s, I lived through inflation of over 30 percent.

That’s a lot, right? Much higher than the latest US CPI increase of 8.6 percent year-over-year (YoY).

What you don’t realize (yet, since I haven’t told you) is that this was not an annual rate. It was in a single month!

The annual inflation rate, in Israel, topped out in 1985 at 486.23 percent! Nearly 57x higher than the latest US number!

That experience gives me a very different perspective on our current inflation woes in the United States.

What Is Hyper-Inflation and What Were the Most Extreme Cases in Modern History?

Philip Cagan of Columbia University defined hyper-inflation in 1956 as monthly price increases of 50 percent. That translates to nearly 13,000 percent YoY, over 1500x higher than our latest YoY increase.

That sounds nearly surreal!

At that rate, the purchasing power of $100 would drop in a single year to only $0.77!

Can that ever happen?

As it turns out, not just can it happen, it can, and actually has been much worse in several countries.

- Argentina in 1989/90 experienced 20,262.80 percent YoY inflation

- Venezuela in 2018/19 suffered 344,509.50 percent YoY inflation

- Yugoslavia from April 1992 to January 1994 hit an equivalent daily inflation of 64.6 percent

- Zimbabwe from March 2007 to mid-November 2008 hit an equivalent daily inflation of 98 percent, nearly doubling prices daily

- Hungary in 1945/46 had an equivalent daily inflation of 207 percent, with prices doubling in 15 hours!

As Matthew Johnston wrote in the above-linked Investopedia article, “The U.S. hasn’t experienced hyperinflation. The inflation rate reached 23 percent in 1920 and 14 percent in 1980 (nowhere near the 50 percent benchmark for hyperinflation).”

I wholeheartedly agree with Johnston.

We’re nowhere near hyperinflation now, our country has never experienced hyperinflation in the past, and it’s highly unlikely to get there in the future.

What’s Happening in the US Now?

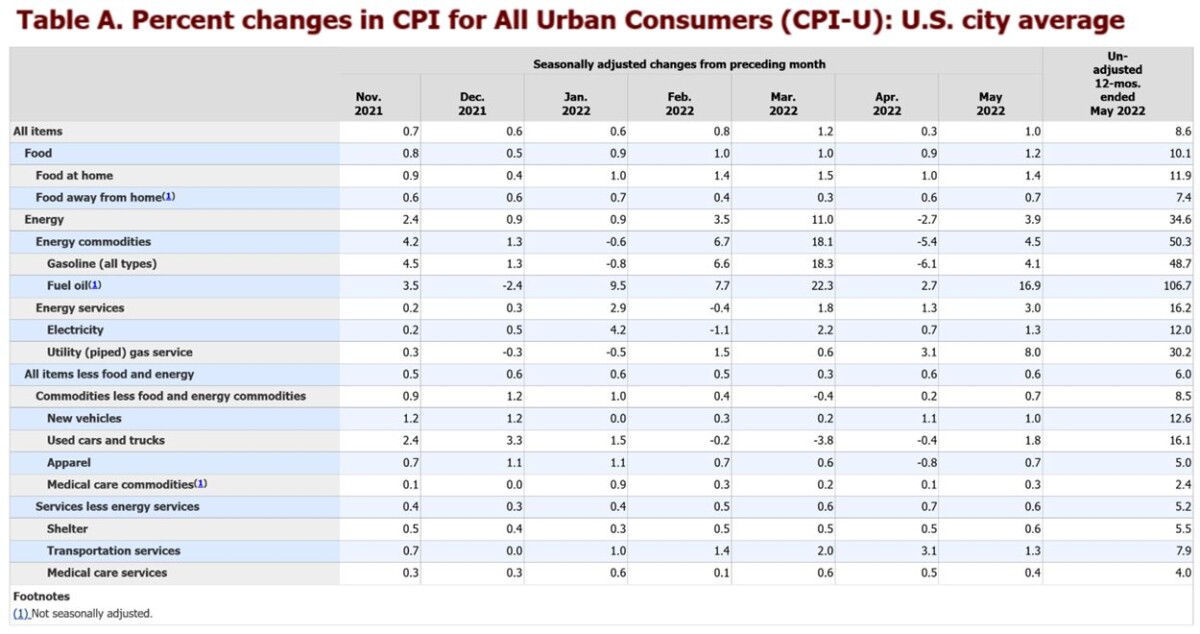

The most recent CPI numbers show a monthly increase of 1.0 percent in May, with a YoY increase of 8.6 percent.

The so-called “core CPI,” which excludes the highly volatile energy and food costs, was 0.6 percent in May, with a 6.0 percent YoY rate.

To see how volatile those non-core sectors can be, the most recent YoY rate for energy was 34.6 percent. Inside the core CPI, the highest YoY increases were recorded (no great surprise) for new and used vehicles, at 12.6 percent and 16.1 percent, respectively (see table below).

How Does this Compare with Historic US Inflation Rate?

According to TradingEconomics.com, US inflation topped out at 23.7 percent in June of 1920. That’s more than 2.75x higher than our most recent rate. In the modern era, inflation was highest in the early 1980s, at 14.8 percent, or 1.7x the latest rate.

In that context, the recent number seems almost tame.

But is it really?

Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers says no.

He claims that a CPI methodology change enacted in 1983 makes comparison with previous high-inflation eras difficult. With economists Bolhuis and Cramer, he developed a methodology to make a more apples-to-apples comparison.

In a recent research paper (Bolhuis, M.A., Cramer, J.N., & Summers, L.H., (2022), “Comparing Past and Present Inflation” (No. w30116), National Bureau of Economic Research), Summers and his co-authors explain that prior to 1983, the CPI accounted very differently for changes in the cost of home ownership.

They write, “…consumers either paid for the home purchase price or the mortgage payments, but not both. Including both [in 1953-1983 CPI data] led to a larger share of housing in the consumption basket…” Specifically, they say the effective weight of “homeownership” on the CPI dropped by nearly half, from 26.1 percent prior to the 1983 change to 13.5 percent after the change.

Why is this important for us today?

Summers et al. state that this different 1953-1983 calculation artificially increased apparent peak inflation rates, and overstated the speed of the drop once the peak passed.

They write, “…we find that current inflation levels are much closer to past inflation peaks than the official [CPI data] suggest…” and later state, “…the rate of core CPI disinflation caused by Volcker-era policies is significantly lower when measured using today’s treatment of housing: only 5 percentage points of decline instead of 11 percentage points in the official CPI statistics. To return to 2 percent core CPI inflation today will thus require nearly the same amount of disinflation as achieved under Chairman Volcker.”

This references Paul Volcker, who chaired the Fed from 1979 to 1987. When he took that position, the greatest challenge was reining in double-digit inflation. Volcker managed to crush inflation down to 3.8 percent by the end of 1982 and maintained it in the range of 1.1 to 4.4 percent for the remainder of his term.

How did Volcker achieve this remarkable feat?

He did it by raising the Fed’s funds rate by 0.5 percent shortly after becoming Chairman, raising it by 4 percent in a single month in October 1979, and allowing it to rise to over 20 percent by June 1981!

Volker’s move pushed home mortgage interest rates to an October 1981 peak of 18.45 percent. For the rest of the 80s, average 30-year-fixed mortgage rates remained in the double digits.

Another result was back-to-back recessions in 1981 and 1982 that led to double-digit unemployment.

Summers et al. estimate that the 14.8 percent March 1980 peak inflation rate would have been just 11.4 percent if recalculated using their proposed methodology. Similarly, the 9.4 percent overall inflation peak of 1949-1954 changes with their methodology to just 3.3 percent; and the 12.3 percent peak of 1972-1976 would be just 9.1 percent.

Thus, in an apples-to-apples comparison to these three modern-era peaks, the recent 8.6 percent reading is second to just one modern-era inflation peak and is over 70 percent of that highest peak.

Assuming Summers, Bolhuis, and Cramer are right, if current Fed Chairman Jerome Powell wants to reverse the current high levels of inflation, he may be forced to increase interest rates to draconian levels, potentially triggering the same economic hardships caused by Volcker’s moves.

Who Are the Winners When Inflation Soars?

The impacts of inflation are many. Here are some of the biggest:

- The cost-of-living increases

- Given that buying something today is likely less expensive than buying it tomorrow, demand increases (to the extent that people can still afford the purchase), to avoid paying those higher future prices; this higher demand puts more upward pressure on prices

- The purchasing power of safe withdrawals from accumulated retirement nest eggs drops

- The value of future corporate profits decreases, putting downward pressure on stock prices

- If your stocks appreciate by the same (e.g., 8.6 percent) rate as inflation, the purchasing power of your portfolio remains flat, but you owe taxes on the 8.6 percent nominal (phantom) gain – this means your portfolio needs to go up to about half again as fast as inflation for you to break even in after-tax terms

- As interest rates rise to account for inflation, (non-inflation-protected) bond prices drop

- The value of fixed annuity payments drops

- As mortgage interest rates go up in response to inflation and the likely increase in the Fed’s funds rate, financing a home purchase becomes more expensive

- The above reduces demand for homes, putting downward pressure on home values

- Even if home prices decrease, that’s likely more than offset by higher interest rates, which in turn pushes up rents

- If rising interest rates cause a deep recession, unemployment can soar

With all these direct and indirect impacts, who loses?

- Anyone with adjustable-rate debt, whether that’s credit card debt or an adjustable-rate mortgage

- Anyone living on a fixed income (e.g., your employer doesn’t give cost-of-living adjustments or COLA raises, or you depend on fixed annuity payments)

- Anyone who needs to sell fixed-rate bonds to pay for their expenses

- Anyone who wants to move, but can’t afford the higher mortgage interest rates, and anyway has a harder time finding buyers

- Anyone who needs to sell stocks when they’re depressed to cover their expenses

- Anyone who has a large taxable portfolio (but not so large that they don’t care about prices going up)

- Anyone who rents their home

- Especially, anyone who could barely scrape by before, and now can’t afford the bare necessities

- Most especially, anyone who loses their job due to a recession triggered by Fed moves to curb inflation, and can’t find a new one making as much or more

Does any of that describe you? Almost certainly.

Now that we know who loses, who wins?

- The ultra-wealthy, because they always win; they have so much money that even if all prices quadrupled tomorrow, they’d barely feel it

- Anyone who owes long-term fixed-rate debts that were previously borrowed at rates substantially lower than current inflation rates; this is especially true for 30-year-fixed mortgages and, to a lesser extent, auto loans, because the real value of the dollars you owe drops with inflation

- Anyone who can command income increases that keep up with inflation or beat it; this includes, e.g., business owners, independent service providers, etc.

- Owners of rental properties, who combine long-term fixed-rate debt with the ability to increase rent

- Anyone who wants to buy a new fixed annuity in a higher-interest-rate environment, since their payments will be much higher relative to the amounts they invest

- Anyone whose income automatically increases such as, e.g., retirees receiving Social Security benefits (assuming their other assets and income don’t drop in value too much), and many local, state, or federal government employees

Does any of that describe you? Some of it likely does.

The Bottom Line

Recent US inflation rates are very far indeed from the sort of hyperinflation historically suffered by multiple other nations.

That’s the good news.

The bad news is that the recent 8.6 percent YoY US inflation is almost within touching distance of the highest it’s been in the modern era, especially if we consider the argument made by Summers and his co-authors.

Realistically, most of us will find that one or more aspects of the “high-inflation-losers” list apply to us, while one or more aspects of the “high-inflation-winners” list also apply to us. For example, you might have a fixed-rate mortgage and/or fixed-rate auto loan, but also variable-rate credit-card debt.

So, given this, are you a high-inflation winner or loser?

That depends on the balance between those different lists as they apply to your personal situation.

If the “high-inflation-loser” aspects outweigh the “high-inflation-winner” ones, you would, unfortunately, be more in the losing category. If the “high-inflation-winner” aspects outweigh the “high-inflation-loser” ones, you’d thankfully be more in the winning category.

Here are 10 things you can do to fight inflation’s effects on your finances:

- Avoid taking out adjustable-rate loans

- Pay off credit card debt as quickly as possible

- Avoid paying off fixed-rate loans (with interest rates lower than inflation) any faster than you must

- Make yourself indispensable at work so you don’t lose your job, and hopefully get a raise

- Look for ways to diversify and increase your income (side hustle anyone?)

- If you own a business and/or provide services, consider increasing your rates to offset inflation

- If you own a rental property, consider raising rents at lease renewals at least enough to counter inflation, but not so much that the new rent becomes unattainable for your renters

- Try to reduce your discretionary spending, at least enough to avoid taking on new debt and/or selling depressed assets (e.g., stocks or bonds that lost value)

- If you can’t reasonably sell your home but have to move, consider buying your next home without selling the old one, and turn that old one into a rental property

- If you’re planning to buy a fixed annuity, consider holding off until higher interest rates push up the offered payments

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only, and should not be considered financial advice. You should consult a financial professional before making any major financial decisions.

About the Author

Opher Ganel, Ph.D.

My career has had many unpredictable twists and turns. A MSc in theoretical physics, PhD in experimental high-energy physics, postdoc in particle detector R&D, research position in experimental cosmic-ray physics (including a couple of visits to Antarctica), a brief stint at a small engineering services company supporting NASA, followed by starting my own small consulting practice supporting NASA projects and programs. Along the way, I started other micro businesses and helped my wife start and grow her own Marriage and Family Therapy practice. Now, I use all these experiences to also offer financial strategy services to help independent professionals achieve their personal and business finance goals. Connect with me on my own site: OpherGanel.com and/or follow my Medium publication: medium.com/financial-strategy/.

Learn More About Opher

Wealthtender is a trusted, independent financial directory and educational resource governed by our strict Editorial Policy, Integrity Standards, and Terms of Use. While we receive compensation from featured professionals (a natural conflict of interest), we always operate with integrity and transparency to earn your trust. Wealthtender is not a client of these providers. ➡️ Find a Local Advisor | 🎯 Find a Specialist Advisor