Wealthtender is a trusted, independent financial directory and educational resource governed by our strict Editorial Policy, Integrity Standards, and Terms of Use. While we receive compensation from featured professionals (a natural conflict of interest), we always operate with integrity and transparency to earn your trust. Wealthtender is not a client of these providers. ➡️ Find a Local Advisor | 🎯 Find a Specialist Advisor

There’s a difference between “being in debt” and “having debt.” You may think the difference is subtle, but it’s anything but…

Wondering how to get your debt payoff priorities right? Let’s dive in.

Being in Debt

Back in 1992, I borrowed $6,000 at 10.4% (!) interest to buy a used car.

As I’ve written elsewhere, that was one of my biggest financial blunders. The $195 monthly payment took up nearly 10% of our income. For three years, that drag on our finances (and my stress levels) was hard to deal with.

Among other things, it meant we couldn’t save and invest anything for those three years.

That’s what being in debt is like.

- You’re stressed

- You have fewer options

- You can’t improve your financial situation (as much)

- If anything bad happens (think job loss), you could end up losing your car and/or your home

Having Debt

Having debt, on the other hand, can be a good thing.

I took out mortgages to buy homes and an office suite. The interest rates are low (far lower than recent inflation numbers, and even less than the 3.82% average inflation since 1871, see below). And, that interest is even tax-deductible.

I also took out low-interest auto loans rather than paying all cash, to avoid needlessly tying up capital.

If I chose to, I could pay off all our debts tomorrow and have plenty left over.

That’s what having debt means.

The Long-Term Financial Impacts of Being in Debt

Remember that 10.4%-interest, three-year auto loan I mentioned above?

Those three years were a missed opportunity.

Had I been savvy enough to buy a $4,000 used car instead of an $8,000 one, we’d have paid $104 total interest (paying the same $195 a month to get out of debt in 11 months) instead of $1,009.

nd since even a used car depreciates about 15% a year, by the end of Year 3, instead of having paid a total of $7009 for a car that by then was worth $4900 (for a net loss of $2100), I’d have paid a total of $4100 for a car that by that point was worth $2450 (for a net loss of $1650).

That would have improved the impact on our net worth by $450. Back then for us, that would have been significant!

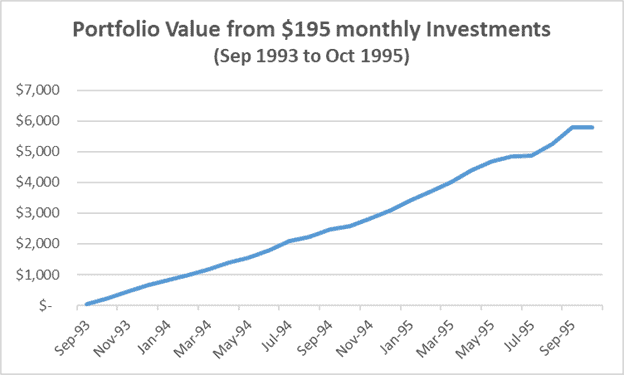

Even better, I’d have been able to invest the $195 a month we no longer had to pay the lender, so we’d have accumulated $5,800 (using actual S&P 500 total return for those 25 months).

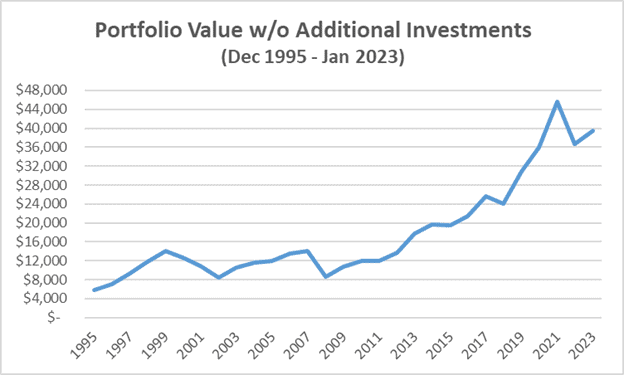

Using actual S&P 500 total returns from December 1995 to January 2023, that investment would have by now grown to $39,500 without investing a single additional dollar.

Yes, inflation would have reduced the value of those dollars to $20,500 in December-1995 dollars, but our total net-worth enhancement would still have been $22,600 in those December-1995 dollars.

Not too shabby, right?

Should We Pay Off Our Current Debts ASAP?

These days, our income is high enough that we could significantly accelerate paying off our three mortgages and two auto loans or even, as mentioned above, pay them all off at once with plenty left over.

But would that be a good financial move?

Hardly! Accelerating mortgage payoff is almost always foolish.

In fact, as I wrote a while back, we’ve actually been making money off our mortgages!

Why would I want to reduce the balances on these loans any faster than required?

Even our auto loans’ interest rates are low enough that the interest they accrue is less than the rate at which the balances lose value to inflation.

However, this isn’t necessarily true for all debts.

Had we carried balances on, say, credit cards with a 20%+ annual interest rate, I’d pay those off as soon as I possibly could, even at the expense of not investing a penny more until they were paid off.

I said as much in a comment I recently left on an article by Shefali O’Hara, “Paying Off Debt Is Not The FIRST Priority.”

How I Prioritize Debt Payoff vs. Investing

Here’s how I look at the relative priority between investing and paying off debt.

Historically, from 1871 to date, stocks returned an average of 10.2% a year, while 10-year bonds returned an average of 5.6% (according to data from Yale economist Robert Shiller).

Adjusting for inflation, those numbers drop to 6.16% and 1.73%, respectively. The difference comes from the higher risk of investing in stocks relative to US government bonds.

Most financial advisors recommend you diversify your investments between risk assets (stocks) and low-risk assets (e.g., bonds), whether that’s 60/40, 70/30, or even 80/20.

Since paying off debt offers the equivalent of a guaranteed “return” equal to the interest rate you pay, it’s reasonable to compare debt payoff to investing in bonds.

Here too, however, adjust the interest on your debt for inflation.

What inflation rate should you use?

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers (CPI-U) for 2022 was 6.5%.

However, that number is misleading because it includes the high inflation of the first six months of 2022 (6.28%, or 12.95% annualized), with the near-zero inflation of the second half of the year (0.16%, or 0.32% annualized).

Thus, since inflation seems to have dropped a lot from its recent multi-decade high, it probably makes sense to use the 3.82% long-term average.

The real “return” you should assume is thus your debt’s interest rate corrected by that 3.82%. Simple subtraction is an easy approximation (where “Int” is your debt’s annual interest rate):

Int — 3.82%

But if you want to be mathematically accurate, use this formula:

[(1+Int)/1.0382]–1

(For 6% interest, e.g., the approximation comes out to 2.18% while the accurate number is 2.1%.)

If your interest rate is 3.82% (or less), your “return” on paying off your debt will be zero (or negative, i.e., a loss).

This doesn’t mean you should stop making payments — that would have dire consequences like repossession, foreclosure, credit-score reduction, and potentially even bankruptcy).

It does, however, mean you shouldn’t pay a penny more than your minimum required payments.

In fact, even if your interest rate is higher but less than bonds’ long-term average of 5.6%, I wouldn’t accelerate paying off such debt.

If your interest rate is above 5.6% it starts making sense to prioritize payoff acceleration.

How about interest rates over 10%?

If you have any such debts, I’d sell off investments to pay them off ASAP, since your guaranteed “return” on paying off the debt is about the same (or better than) your average (but uncertain) risk-asset return.

What the Pros Say

Christopher J. Berry, JD, CFP, CELA, founder, Castle Wealth Group says, “I first look at the interest rate. Generally, if it’s under 4% (say a mortgage or student loan), I lean towards not paying off the debt faster, since the money could be invested and earn a higher rate. Think of it like a bucket – if 3% is going out but 5% is coming in, the bucket is still filling up. However, if the interest rate is over 4%, I lean towards paying off the debt faster.”

Michael R. Acosta, CFP, ChFC, CSLP, Financial Planner at Genesis Wealth Planning agrees, “First, I consider and review with clients the type of debt we’re dealing with. In other words, is it a ‘good or valuable’ debt, or is it a ‘bad’ debt? We then compare the current interest rate to the expected return on investment. If we believe we can obtain a better return elsewhere vs. sending these dollars to someone else’s balance sheet, we’ll invest. If there isn’t like or higher return to be made elsewhere, we’ll pay the debt off more aggressively. We also consider any value added by the debt, such as interest tax deduction, etc.”

David Barfield, CFP, Founder / Financial Planner, Datapoint Financial Planning elaborates, “Often, the decision to pay down debt or invest comes down to one’s debt tolerance. However, my general guideline to clients is to get any free money offered by their employer, like the 401(k) match, before addressing the debt, if possible. Once the free money is secured, I want them to knock out any high-interest debt.

“I typically won’t advise clients to pay down mortgages or low-interest car loans faster until they have an adequate emergency fund, have maxed out all tax-advantaged accounts, and are saving at least 25% of gross income toward long-term goals.

“I charge a flat fee that doesn’t fluctuate based on assets, so I have no conflicts around clients investing more vs. paying off their mortgage early. But paying off a low-interest home loan at the expense of saving for the future is not a winning formula in most cases.”

Jon McCardle, AIF, President Summit Financial Group of Indiana says, “We have this conversation at least monthly with clients of all levels of income and net worth. We advise them based on three elements: (1) their income vs. debt payments, (2) how far they are from their target retirement assets vs. how long they have until retirement, and (3) if debt reduction is one of their top three goals. Especially if they say debt reduction is a top-three goal, interest rates aren’t the focus, paying off debt is.”

Daryoosh Khalilollahi, CFP, MBA, MSEE, Principal and Financial Planner at DABK Financial Planning Services points out that, “There are two important differences between making, say, 6% on your money and avoiding 6% interest on a loan. First, the former is expected but could be (more or) less, but the latter is guaranteed. Second (unless the loan interest is tax-deductible), investment returns are worth less than avoiding the same percentage interest. E.g., if your total marginal tax rate (Federal, state, and local) is 33.3%, a 6% taxable return is worth just 4% (67% of 6%), whereas the 6% interest you avoid is all yours.”

The Bottom Line

When you owe money and are paying interest on it, you’re usually required to make minimum monthly payments.

Depending on the interest rate, it may make sense to pay just that minimum, accelerate payoff, or even sell investments to pay it off ASAP.

Here’s how I prioritize things:

- For interest rates equal to or lower than the return on long-term bonds (let alone where the real interest is negative), I pay only the minimum, and invest any extra leftover funds

- For interest rates higher than the return on long-term bonds up to about 9–10%, I accelerate payoff at the expense of not investing

- For interest rates above 10% (that I try to avoid), I’d sell investments to pay off these high-interest debts ASAP!

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only, and should not be considered financial advice. You should consult a financial professional before making any major financial decisions.

About the Author

Opher Ganel

My career has had many unpredictable twists and turns. A MSc in theoretical physics, PhD in experimental high-energy physics, postdoc in particle detector R&D, research position in experimental cosmic-ray physics (including a couple of visits to Antarctica), a brief stint at a small engineering services company supporting NASA, followed by starting my own small consulting practice supporting NASA projects and programs. Along the way, I started other micro businesses and helped my wife start and grow her own Marriage and Family Therapy practice. Now, I use all these experiences to also offer financial strategy services to help independent professionals achieve their personal and business finance goals.

Connect with me on my own site: OpherGanel.com and/or follow my Medium publication: medium.com/financial-strategy/.

Wealthtender is a trusted, independent financial directory and educational resource governed by our strict Editorial Policy, Integrity Standards, and Terms of Use. While we receive compensation from featured professionals (a natural conflict of interest), we always operate with integrity and transparency to earn your trust. Wealthtender is not a client of these providers. ➡️ Find a Local Advisor | 🎯 Find a Specialist Advisor