Wealthtender is a trusted, independent financial directory and educational resource governed by our strict Editorial Policy, Integrity Standards, and Terms of Use. While we receive compensation from featured professionals (a natural conflict of interest), we always operate with integrity and transparency to earn your trust. Wealthtender is not a client of these providers. ➡️ Find a Local Advisor | 🎯 Find a Specialist Advisor

As lawmakers like to do, they tucked into a must-pass bill some last-minute changes to the tax code.

These specific changes will hurt retirement planning even for the middle class.

The so-called “Secure Act” was inserted into a $1.4 trillion spending bill that had to pass to avoid another government shutdown. President Trump signed the bill into law on December 20.

Here’s how the new law is supposed to help you, how it actually hurts you, and what you can do to minimize the damage.

How the Secure Act Is Supposed to Help

The new law makes it easier for small-business owners to provide retirement benefits to part-time employees. It also includes a way for several small businesses to set up a joint retirement plan for their employees, splitting costs between the different businesses.

However, many workers who can already contribute to a 401(k) plan don’t do so, even when employers offer matching contributions. So why would anyone expect this new package to make much of a difference? Especially for part-time employees who likely make too little to be able to set aside much for retirement.

The “Stretch IRA” Helped the Wealthy, but the Middle Class Too

One of the best ways for parents to leave bequests to their children is by leaving unused balances in retirement plans. A child inheriting parents’ retirement plans could maximize lifetime income from these by withdrawing only the Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs). The RMD is intended to limit how long he can put off paying taxes on those balances. However, according to pre-Secure-Act law, a non-spouse beneficiary (e.g., an adult child) could stretch out the draw-down over his lifetime.

An Example Scenario

To see how this works, let’s start with some assumptions:

- A parent dies at age 75, leaving behind $1 million in a traditional IRA.

- The beneficiary is his 45-year-old son whose household income is the median income for MD, and who deducts the standard deduction on his married-filing-jointly tax returns.

- The portfolio earns 9.965% annually (according to data from Yale’s Case and Shiller, this is the annualized return of US stocks from 1926 to 2019).

- Tax brackets for federal, Maryland state, and local income taxes keep up exactly with inflation.

- All amounts adjusted for 2.88% annual inflation (from Case and Shiller data for the above period).

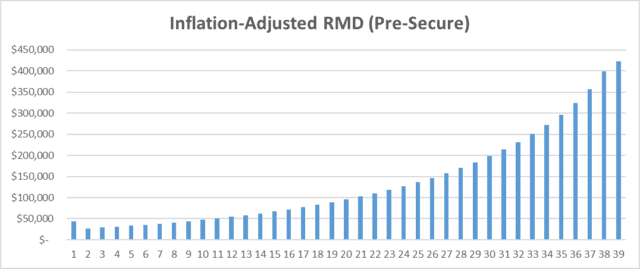

Using data from a Charles Schwab RMD calculator, here’s the inflation-adjusted RMD over the beneficiary’s 39-year life expectancy.

Inflation-adjusted RMD from a hypothetical million IRA inherited by a 45-year-old man from a parent, based on a 9.965%. Data from Charles Schwab RMD calculator.

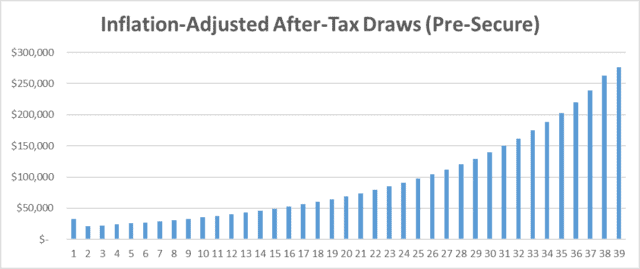

I started from the $81,868 median household income for Maryland per the Census Bureau. Next, I added each year’s inflation-adjusted RMD. Then, I estimated the excess federal, state, and local income taxes for the RMD amounts each year. Reducing the RMD by these taxes, we find inflation-adjusted after-tax amounts left for the beneficiary as shown below. The total over 39 years is $3.7 million after taxes.

Inflation-adjusted after-tax income from the above RMDs.

How the Secure Act Can Cost You over $2.5 Million!

To help fund the expected costs of the Secure Act, legislators prevented the above “stretch IRA” technique if the parent dies after Dec 31, 2019. Instead, they allow only a 10-year window to draw down the inherited IRA in full. A penalty of 50% is assessed on any amounts left in the IRA after that. The new law does let the beneficiary decide how much to draw each year. The only requirement is that the account be empty after 10 years. Interestingly, the same window and penalty apply to Roth accounts even though contributions to those were made after tax.

To see the impact of the new rules, I redid the above calculations for the same assumptions but drawing down the account within 10 years. I did this both with equal annual draws of $149,338 (inflation adjusted), or drawing nothing for the first 9 years and draining the account in the 10th year by drawing $2,084,471 (inflation-adjusted).

The first strategy results in an extra inflation-adjusted net income of $1.06 million. The second strategy does somewhat better at $1.18 million. Compared to the $3.7 million net inflation-adjusted income of the stretch IRA technique, under the Secure Act you lose $2.65 million if you draw down the account in equal annual amounts, and $2.53 million if you hold off to the last minute!

The Congressional Budget Office estimated in April that this change would bring in an extra $16 billion in new federal income taxes over the next decade.

Guess who’ll pay those extra billions…

What You Can Do About This

If you’re the beneficiary in the above scenario, there isn’t much you can do to reduce the impact beyond maximizing whatever tax-deferral options are available to you. These include:

- Maxing out contributions to your own IRAs, 401(k) plans and other employer retirement plan, as well as those of your spouse.

- Maxing out contributions to a Health Savings Account (HSA), assuming your health insurance plan is HSA-compatible.

- If you own a small pass-through business, making sure to take full advantage of the 20% Qualified Business Income Deduction (QBID).

If you’re the parent in our scenario, you should consult with your financial planner to maximize your beneficiaries’ after-tax inheritance.

Some things to consider include:

- The above changes don’t apply to your surviving spouse, minor children, disabled or chronically ill beneficiaries, or anyone within 10 years of your own age.

- Converting your traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs may result in a higher after-tax bequest. This would require you to pay more taxes before you die, but no taxes would be due on the amounts you leave to your beneficiaries. However, as mentioned above, they’d still need to drain those accounts within 10 years of your death.

You Might Also Enjoy:

The Bottom Line

The new Secure Act that was supposed to help you will more than likely hurt you if you’re expecting to inherit a substantial IRA, even if your income isn’t much above the median.

There are a few moves you can make as the parent who plans to leave IRAs to your beneficiaries when you die. There are also (fewer) things you can do if you’re the beneficiary.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only, and should not be considered financial advice. You should consult a financial professional before making any major financial decisions.

About the Author

Opher Ganel, Ph.D.

My career has had many unpredictable twists and turns. A MSc in theoretical physics, PhD in experimental high-energy physics, postdoc in particle detector R&D, research position in experimental cosmic-ray physics (including a couple of visits to Antarctica), a brief stint at a small engineering services company supporting NASA, followed by starting my own small consulting practice supporting NASA projects and programs. Along the way, I started other micro businesses and helped my wife start and grow her own Marriage and Family Therapy practice. Now, I use all these experiences to also offer financial strategy services to help independent professionals achieve their personal and business finance goals. Connect with me on my own site: OpherGanel.com and/or follow my Medium publication: medium.com/financial-strategy/.

Learn More About Opher

Wealthtender is a trusted, independent financial directory and educational resource governed by our strict Editorial Policy, Integrity Standards, and Terms of Use. While we receive compensation from featured professionals (a natural conflict of interest), we always operate with integrity and transparency to earn your trust. Wealthtender is not a client of these providers. ➡️ Find a Local Advisor | 🎯 Find a Specialist Advisor